There is a particular philosophy of cooking that Ina Garten has spent her entire career articulating, and it is a philosophy that runs directly counter to the most common instinct of the ambitious home cook. Where most of us reach for complexity — more ingredients, more techniques, more layers of intervention — Garten reaches for restraint. Her argument, made recipe after recipe across decades of Barefoot Contessa cookbooks and television, is that the highest form of culinary intelligence is the ability to recognize when the ingredients in front of you are already extraordinary, and to do exactly and only what is necessary to make them taste like themselves at their very best. Linguine with Shrimp Scampi Recipe is the purest expression of this philosophy in her repertoire. It is, at its structural core, an astonishingly simple dish: shrimp and pasta, dressed in a sauce of garlic-infused butter and olive oil, brightened with fresh lemon and finished with parsley. Six primary ingredients. Ten minutes of active cooking. And the result, when the technique is correct and the ingredients are genuinely good, is something that belongs on the table of a Hamptons dinner party as naturally and confidently as it belongs on a Tuesday night kitchen table.

What separates Garten’s version from the dozens of lesser shrimp scampi recipes that populate the culinary internet is the combination of two things: the technical intelligence of the butter-and-oil approach to the cooking fat, and the discipline of the timing. The olive oil in the cooking fat raises the effective smoke point of the mixture above what butter alone could sustain, preventing the milk solids in the butter from scorching before the garlic has had time to infuse the fat properly. The garlic goes in first — alone in the hot fat for exactly one minute — and only then do the shrimp follow, entering a pan that is already richly infused with garlic aromatics throughout the fat. The shrimp cook for three to five minutes maximum. The pasta, already cooked just to al dente, finishes in the pan — not on the plate, in the pan — where its surface starch bonds with the butter and shrimp fat to create a light, clingy, cohesive sauce that coats every strand rather than pooling at the bottom of the serving bowl. Then the lemon — both zest and juice — and the parsley, and it is done. The entire active cooking process from first garlic to final toss takes no longer than twelve to fifteen minutes.

This is not a recipe that hides behind complexity. Every ingredient is present and accountable. There is no cream to mask imperfect timing, no elaborate spice blend to compensate for mediocre shrimp. What you put in is exactly what you get back, which is precisely why using the best ingredients available and executing the technique correctly are not optional considerations but the entire point. Understood this way, this recipe is not simple at all — it is demanding in the very specific way that all truly honest cooking is demanding: it requires you to be good, because there is nowhere to hide. Get the shrimp fresh, the garlic fresh, the lemons fragrant and heavy with juice, the butter cold and unsalted. Then get out of the way and let them be what they are.

Recipe Overview

| Detail | Info |

|---|---|

| Cuisine | Italian-American |

| Course | Main Course |

| Difficulty | Easy |

| Servings | 4 |

| Prep Time | 15 Minutes |

| Cook Time | 10 Minutes |

| Calories per Serving | Approx. 580 kcal |

Ingredients

The Pasta:

- 1 lb dried linguine

- Kosher salt (generous — the water should taste like mild seawater)

- Splash of olive oil for the pasta water

The Sauce and Shrimp:

- 3 tbsp good-quality extra-virgin olive oil

- 3 tbsp unsalted butter

- 1½ tbsp fresh garlic, minced (approximately 4–5 medium cloves)

- 1 lb large or extra-large shrimp (16/20 count), peeled and deveined

- Kosher salt and freshly ground black pepper

The Finishing Elements:

- Zest of 1 large lemon (zested before juicing)

- Juice of 1 large lemon

- ¼ tsp red pepper flakes (or to taste)

- Generous handful of fresh flat-leaf parsley, finely chopped

The Garnish:

- Thin lemon slices

- Additional parsley, if desired

Step-by-Step Instructions

Step 1 — The Pasta Foundation: Water, Salt, and Timing

Fill the largest pot you own with cold water and bring it to a rolling, aggressive boil over high heat. The pot size matters: linguine is a long pasta that needs substantial water volume to cook evenly and move freely without clumping during the boil. When the water reaches a full rolling boil, add a generous tablespoon of kosher salt — generous enough that the water tastes pleasantly salty when tasted, like a well-seasoned broth rather than seawater. This salting is the pasta’s only opportunity to be seasoned from within: salt diffuses through the pasta’s surface during cooking, seasoning the interior starch matrix in a way that no amount of sauce applied afterward can replicate. Unsalted pasta, regardless of how well the sauce is seasoned, will always taste flat at its core.

Add a small splash of olive oil to the pasta water and immediately add the linguine, fanning the strands into the boiling water and pushing them under as they soften. The olive oil helps the strands remain mobile in the water during the first minutes of cooking, reducing the tendency for long pasta to mat together during the critical early cooking phase. Cook according to the package directions — typically 8 to 10 minutes — but begin tasting two minutes before the package timer expires. You are cooking to al dente: the pasta should offer a slight, pleasant resistance when bitten — firm at the very center without any raw, floury taste. Remember that the pasta will continue cooking when it joins the hot sauce in the pan, so intentional undercooking by 1 to 2 minutes of the package time is correct rather than a mistake. Before draining, reserve a cup of the starchy pasta cooking water — this liquid is one of the most valuable tools in the pasta cook’s arsenal and is used to adjust sauce consistency in the final toss.

Step 2 — The Aromatic Base: Building the Fat Foundation

While the pasta is cooking, begin the sauce in a wide, heavy-bottomed skillet — a pan with maximum surface area relative to its depth, which provides more even heat distribution and more space for the shrimp to cook in a single uncrowded layer. Over medium heat, add the olive oil and butter together simultaneously. The combination of these two fats is not merely additive — it is synergistic. Butter alone has a smoke point of approximately 302–350°F (150–177°C), limited by its milk solid content which begins browning, then burning, at these relatively low temperatures. Olive oil, added in equal proportion, both raises the effective smoke point of the mixture and provides its own flavor dimension — the bright, slightly fruity, grassy character of good extra-virgin olive oil — that pure butter cannot provide. The butter, in turn, provides the primary sauce body and the creamy, rich mouthfeel that olive oil alone is too thin to deliver. Together they create the ideal cooking medium: stable at medium heat, rich in flavor, and beautifully velvety in texture.

Once the butter is fully melted and the fat mixture is shimmering but not smoking, add the minced garlic in a single motion. The garlic must now be given exactly one minute of undivided attention — stir it continuously and keep it moving throughout the fat, monitoring its color and aroma constantly. You are looking for the point at which the garlic is fragrant, translucent, and just barely beginning to turn the faintest gold at the very edges of the smallest pieces — this is the flavor sweet spot at which the garlic’s harsh raw pungency has been cooked away and its sweetness and complexity have fully developed, but before the Maillard browning products have crossed from pleasantly savory into acrid and bitter. This transition happens in seconds at this temperature, and there is no recovering from burned garlic — the bitter compounds it produces cannot be removed from the fat and will define the flavor of everything that follows. One minute, medium heat, continuous stirring, and immediate attention when the first hint of gold appears.

Step 3 — Searing the Shrimp: Speed and Single Layer

If your shrimp are cold from the refrigerator, bring them to room temperature for 15 to 20 minutes before cooking — a cold shrimp dropped into a hot pan drops the pan’s temperature significantly and shifts from searing to steaming, which produces a pale, rubbery, steamed shrimp rather than a properly seared one. Pat the shrimp completely dry with paper towels before they enter the pan: surface moisture is the enemy of searing — it creates a steam layer between the shrimp surface and the hot pan that prevents the Maillard reaction from occurring until all of that moisture has evaporated.

Add the shrimp to the pan in a single, uncrowded layer — if they overlap or crowd each other, the pan temperature drops and steam accumulates between the pieces, again shifting from searing to steaming. Season immediately with salt and black pepper. Cook for approximately 2 minutes on the first side without moving them, allowing a slight crust to develop. Flip each shrimp once and cook for 1 to 2 minutes more on the second side. The window between correctly cooked and overcooked shrimp is narrow and unforgiving: the visual cue is the color change from translucent gray-blue to opaque pink-white, which signals protein denaturation throughout the flesh. When the shrimp have just turned fully pink and opaque but still have a slight springiness when pressed — rather than the dense, firm compression of an overcooked shrimp — they are done. Remove the pan from the heat immediately if the pasta is not yet ready, and allow the residual heat of the pan to finish the shrimp gently while you complete the pasta.

Step 4 — The Flavor Emulsion: Pasta Meets Sauce

Drain the al dente linguine through a colander, shaking briefly to remove excess water but not draining so thoroughly that every trace of surface moisture is eliminated — a small amount of the starchy surface water is valuable in the pan. Do not rinse the pasta: rinsing washes away the surface starch that is the sauce’s most important bonding agent. Transfer the drained linguine directly into the skillet with the shrimp and garlic-butter sauce, placing the pan back on medium-low heat.

Toss the pasta and sauce vigorously using two large kitchen spoons or tongs, working with a continuous lifting-and-turning motion that coats every strand in the butter-olive oil mixture. As the pasta is tossed in the pan over this gentle heat, the surface starch on the pasta strands interacts with the fat in the sauce — the starch granules, still partially hydrated from cooking, dissolve slightly at the pasta surface and integrate with the butter’s emulsified fat phase, thickening the sauce and creating a light, clingy coating that adheres to the pasta rather than dripping from it. This is the technique that differentiates pasta that is dressed in sauce from pasta that has absorbed and become part of a sauce — and it is accomplished entirely within the pan rather than in a serving bowl. If the sauce appears too thick or the pasta too dry at this stage, add 2 to 3 tablespoons of the reserved pasta cooking water and toss again — the water’s dissolved starch will loosen the sauce while simultaneously adding additional starch-based body.

Step 5 — Brightening the Dish: The Lemon and the Parsley

With the pasta and sauce united in the pan over low heat, add the lemon zest, lemon juice, and red pepper flakes in a single addition and toss immediately to distribute them throughout. The lemon provides this dish’s most important flavor dimension: the counterweight of high acidity against the butter’s rich, coating fat. Without this acidic brightness, shrimp scampi becomes a pleasant but slightly one-dimensional butter pasta — the lemon is not a garnish or an accent but a structural flavor element that defines the dish’s identity. The zest and the juice serve different roles: the juice provides the primary acidity (from citric acid), which cuts through the fat and stimulates salivation; the zest provides the aromatic essential oils (primarily limonene and linalool) that give the dish its intensely lemony fragrance — a dimension that juice alone cannot provide because the essential oils are fat-soluble compounds located in the peel’s oil glands rather than in the acidic juice. Add the finely chopped fresh parsley and toss one final time to distribute it evenly throughout the pasta.

Step 6 — Serve Immediately

Transfer to warmed serving plates or a large serving bowl and garnish with thin lemon slices arranged decoratively around the edge. This dish does not hold — the sauce will tighten and the shrimp will toughen within minutes of leaving the pan, and no amount of reheating restores the dish to its just-cooked state. Serve it the moment it is plated, with crusty bread for capturing the sauce that pools at the plate’s edges, and a glass of crisp white wine that has been opened and poured before you began cooking.

Conclusion: The Discipline of Simplicity

Ina Garten’s Linguine with Shrimp Scampi is proof that the most sophisticated cooking is often the most restrained. In a culinary landscape that frequently equates complexity with quality — more ingredients, more steps, more equipment, more intervention — this recipe argues the opposite with quiet confidence: that when every ingredient is doing its job correctly, nothing more is needed. The shrimp bring their natural sweetness and briny depth. The garlic-infused butter brings richness and aromatic backbone. The lemon brings the brightness that makes the whole dish feel alive and fresh rather than heavy. The parsley brings a grassy, clean finish that clears the palate for the next bite. And the pasta brings starchy body that unifies everything into a cohesive, sauce-coated whole rather than a collection of disparate elements served in the same bowl.

The technical keystone of the recipe — the emulsification of the pasta’s surface starch with the butter-olive oil fat in the pan — is the single technique that elevates a home cook’s shrimp scampi from “good” to genuinely excellent, and it requires only the discipline of tossing the pasta in the pan rather than simply saucing it in the bowl. This distinction seems minor until you experience the difference in the finished dish: pasta that has been tossed in the sauce in the pan has a unified, silky, clingy coating that makes every strand taste of the sauce throughout its length. Pasta dressed in a bowl is unevenly coated, with some strands swimming in sauce and others barely touched, the sauce pooling at the bottom rather than distributed throughout. The pan toss is the restaurant technique that makes restaurant pasta taste different from home pasta, and it costs nothing but the awareness that it should be done.

At approximately 580 calories per serving, this dish is satisfying and generous without being excessive — a complete meal of meaningful protein from the shrimp, complex carbohydrates from the linguine, and healthy monounsaturated fat from the olive oil, all in a format that takes no longer to produce from start to finish than the time it takes to boil the pasta. Pour the white wine before you begin cooking. Everything else takes care of itself.

Linguine with Shrimp Scampi

Garlic-butter shrimp, lemon zest + juice, and parsley tossed into glossy, clingy linguine

- 1 lb dried linguine

- Kosher salt (water should taste like mild seawater)

- Splash of olive oil (optional) for pasta water

- 3 tbsp extra-virgin olive oil

- 3 tbsp unsalted butter

- 1½ tbsp fresh garlic, minced (4–5 cloves)

- 1 lb large shrimp (16/20), peeled & deveined

- Kosher salt + black pepper, to taste

- Zest + juice of 1 large lemon

- ¼ tsp red pepper flakes (or to taste)

- Generous handful parsley, finely chopped

- Thin lemon slices + extra parsley (optional)

Boil & Salt the Pasta Water

Bring a large pot to a rolling boil. Salt generously. Add linguine and cook 1–2 minutes shy of al dente; reserve 1 cup pasta water.

Build the Garlic-Butter Base

In a wide skillet over medium heat, melt butter with olive oil. Add garlic and stir constantly ~1 minute until fragrant (no browning).

Sear the Shrimp

Pat shrimp dry; cook in a single layer. Season with salt/pepper. Sear ~2 min, flip, cook 1–2 min until just pink and opaque.

Toss Pasta into Sauce

Add drained linguine to the skillet. Toss vigorously over low heat to emulsify. Add splashes of reserved pasta water as needed.

Lemon, Heat, Parsley

Add lemon zest, lemon juice, and red pepper flakes; toss. Add parsley and toss once more.

Serve Immediately

Plate right away. Garnish with lemon slices and extra parsley if desired (this dish is best the moment it’s tossed).

Common FAQs about Linguine with Shrimp Scampi Recipe

Why does this recipe categorically prohibit using jarred or pre-minced garlic?

Fresh garlic’s flavor depends entirely on the enzymatic production of allicin at the moment of cellular disruption — the alliinase enzyme and its alliin substrate are stored in separate cellular compartments and only come into contact (and react to produce allicin) when the cell walls are broken by cutting. Jarred or pre-minced garlic has already undergone this enzymatic reaction at the time of processing, and the allicin produced has already converted to its secondary products — many of which have continued degrading in the acidic, wet environment of the jar, producing sulfur compounds with a flat, stale, slightly sour character that bears little resemblance to the bright, volatile, complex aromatics of freshly cut garlic. For a dish in which garlic is the single most important flavor-building step, using pre-minced garlic produces a fundamentally inferior aromatic foundation.

What is the specific function of pasta surface starch in the emulsion formed during the pan toss?

During the pasta’s cooking, the outer starch granules on the linguine’s surface gelatinize — they absorb water, swell, and partially rupture, releasing amylose and amylopectin chains into both the pasta water and onto the pasta’s surface as a sticky, hydrophilic coating. When the drained pasta is added to the butter-olive oil mixture and tossed over heat, these surface amylose and amylopectin chains interact with the fat at the oil-water interface — the hydrophilic ends of the starch chains associate with the aqueous phase while the less hydrophilic chain segments associate with the fat droplets, acting as a natural emulsifier that stabilizes the fat-water mixture into a unified, creamy sauce rather than allowing it to separate into greasy pools. This starch-emulsified sauce clings to the pasta surface rather than dripping from it, because the starch network physically connects the sauce to the pasta’s own starch-coated surface.

What is the culinary and chemical distinction between lemon zest’s contribution and lemon juice’s contribution to this dish?

emon juice is an aqueous solution of citric acid (approximately 5–8% by weight), water, and various water-soluble flavor compounds. Its primary contribution to this dish is acidity — the citric acid provides the sharp, bright, mouth-watering sourness that cuts through the butter’s fat and prevents palate fatigue from the sauce’s richness. Lemon zest, by contrast, is the outermost layer of the lemon peel — the flavedo — which contains oil glands densely packed with essential oils, primarily limonene (approximately 65–70% of the essential oil), linalool, citral, and various other monoterpenes. These compounds are fat-soluble and highly volatile, producing the intensely lemony, almost floral fragrance that is far more dimensionally complex than any concentration of lemon juice can provide. When the zest is added to the hot, fat-containing pasta, the limonene and other essential oils dissolve into the butter phase and distribute throughout the dish, providing an aromatic brightness that fills the entire plate’s headspace.

What is the historical origin of “scampi” as a dish name and why does the American usage differ from its Italian original?

In Italian culinary tradition, “scampi” (singular: scampo) refers to Nephrops norvegicus — the Norway lobster or Dublin Bay prawn, a small lobster-like crustacean native to the northeastern Atlantic and Mediterranean. Traditional Italian “scampi” preparations involve these specific crustaceans prepared in a garlic-butter-white wine sauce — the preparation style, not the animal, that gave the dish its name. When Italian-American restaurants began adapting this preparation in the United States during the mid-20th century, Norway lobsters were unavailable and unaffordable compared to the abundant Gulf and Atlantic shrimp of the American market. Shrimp — a completely different crustacean species — were substituted in the preparation, but the dish retained the “scampi” name referring to the cooking style (garlic, butter, white wine, parsley) rather than the original seafood. In American culinary parlance, “scampi” has therefore become a preparation descriptor — “shrimp scampi” means shrimp prepared in the scampi style — rather than a reference to any specific animal.

What is the specific argument for large or extra-large shrimp (16/20 count) over smaller shrimp for this recipe?

Shrimp count designations (16/20, 21/25, 31/40, etc.) indicate the number of shrimp per pound at that size — 16/20 means 16 to 20 shrimp per pound, making them “extra-large.” Larger shrimp have a higher meat-to-surface-area ratio than smaller shrimp, which produces two practical advantages in a pan-seared preparation. First, they take longer to overcook — the additional mass means the interior reaches the overcooked-protein threshold more slowly than a small shrimp of equivalent pan temperature, providing a larger window for perfect doneness. Second, they provide more textural interest per piece — a large shrimp has a distinct chew and presence in the dish; a small shrimp (31/40 or smaller) can disappear into the pasta’s texture without providing the substantial, identifiable bites of seafood that the dish’s visual and textural concept requires.

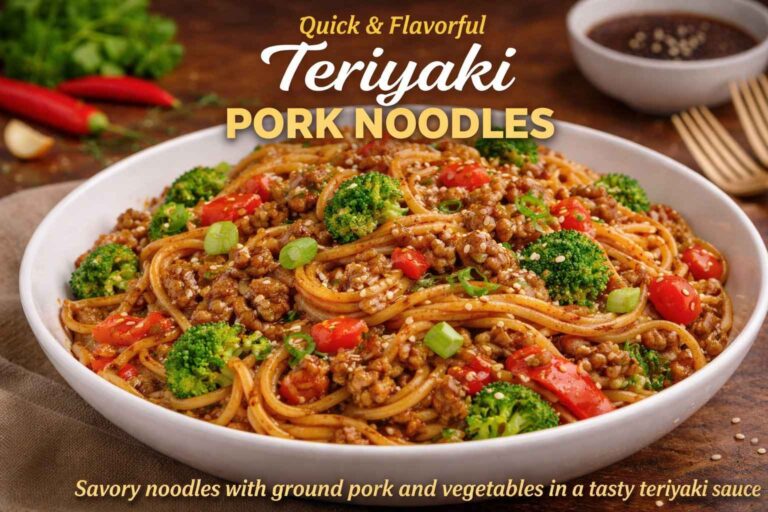

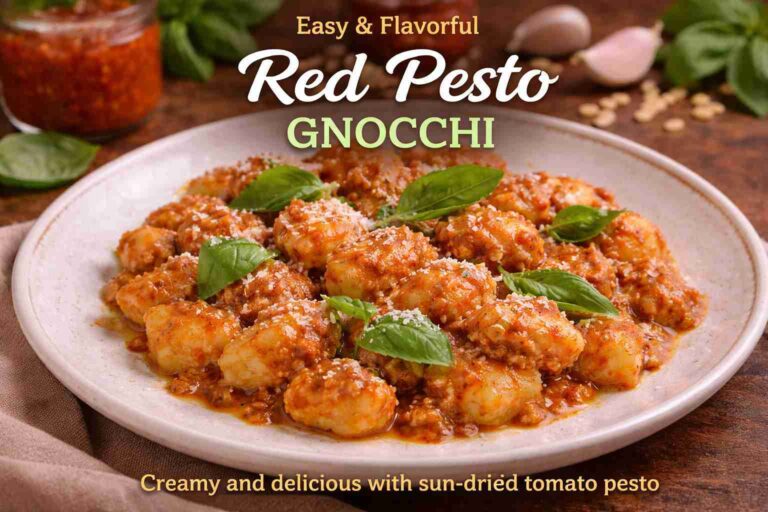

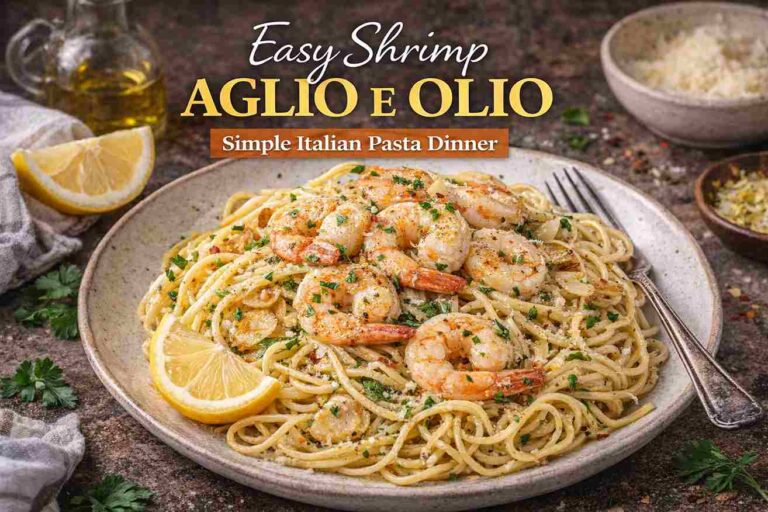

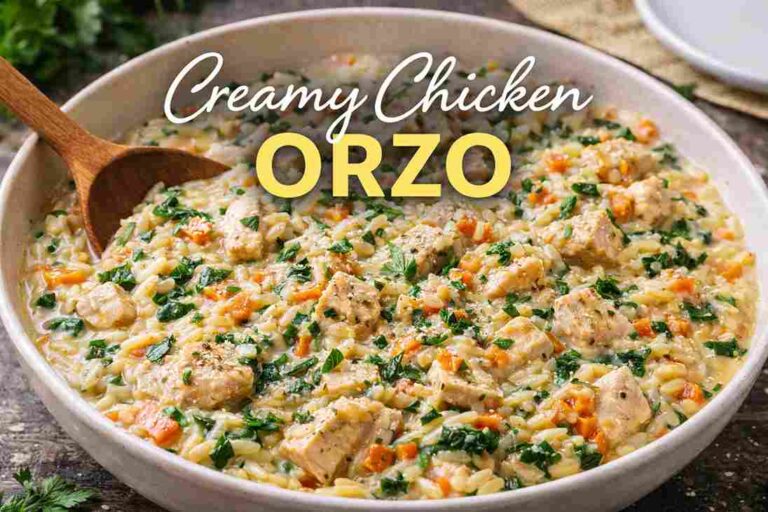

Discover an even more extensive selection of culinary creations spanning every meal and occasion imaginable. Begin your day with our five egg breakfast ideas, chili crisp egg avocado toast, and protein powder cinnamon rolls. For healthier morning choices, try healthy oatmeal apple banana cake, coconut cove baked oatmeal, and blueberry apple morning oats cake. For lunch, savor our ultimate big mac salad, quick ham and cheese pinwheels, crispy potato tacos, and vegan bulgogi pinwheels. Our impressive main courses include Vietnamese lemongrass chicken, honey balsamic pomegranate glazed chicken, mushroom stuffed chicken breast, baked French onion chicken, and low carb Tuscan chicken bake. Meat enthusiasts will delight in three Italian style meatloaves, pan seared pork tenderloin in creamy peppercorn gravy, citrus glazed roasted pork ribs with creamy mushroom potatoes, beef bourguignon, sausage ragu, and Korean sweet spicy beef meatballs. For pasta and seafood lovers, explore shrimp aglio e olio, creamy chicken meatball orzo, red pesto gnocchi, one pan Tuscan orzo with chicken, creamy peri peri chicken pasta, teriyaki pork noodles, one pan chicken chorizo orzo, and brown butter and sage mezzi rigatoni. Our soup collection spans creamy broccoli and garlic soup, carnival squash soup with turmeric, split pea soup, ham bean soup, hearty vegetable barley soup, creamy asparagus soup, French cream of chestnut soup, classic Provençal fish soup, New England creamy clam chowder, and Manhattan clam chowder soup. Vegetarian delights include vegan ramen, quick vegan lasagna, vegan cabbage rolls, spicy maple tofu rice bowl, and vegan chicken and dumpling soup. Side dishes shine with garlic butter cheese bombs, oven baked potatoes with meatballs and cheese, broccoli recipes that taste amazing, oven roasted crispy potato, honey butter cornbread, and 3-ingredient carnivore bun. Appetizers feature the ultimate crispy buffalo chicken wonton cups, the ultimate buffalo chicken cauliflower dip, the ultimate buffalo chicken garlic bread, garlic parmesan wings, brown sugar bacon wrapped smokies, Philly cheesesteak stuffed rolls, bacon cheeseburger dip, and pepperoni pizza dip. Desserts range from blueberry tiramisu and heavenly molten mini chocolate lava cakes to thin and chewy chocolate chip cookies. Special occasion treats include red velvet cookies, Valentine heart cookies, ombre heart buttercream cake, and homemade Valentine’s day mini cake delight. Keto enthusiasts can enjoy keto schnitzel, sugar free keto German chocolate cake, keto yogurt almond cake, keto beef roulades, fluffy keto cloud bread, keto muffins, Korean marinated eggs, and low carb cottage cheese ice cream. Health-conscious options also feature sugar free oat cakes and sugar free banana oat brownies. For cocktail lovers, explore our collection including classic whiskey sour, hot apple whisky lime cocktail, easy margarita, Paloma tequila cocktail, vodka cranberry cocktail, Angel Face cocktail, Mandarin Sunrise cocktail, Aperol Spritz, homemade Piña Colada, virgin Piña Colada mocktail, Moscow Mule, Old Fashioned, Manhattan cocktail, Pomegranate Gimlet, Southside gin cocktail, Paper Plane cocktail, Mango Chilli Margarita, and our ten best rum cocktails. This comprehensive collection ensures there’s a perfect recipe for every craving, celebration, and culinary occasion.